California has a new plan to decarbonize industry

Quitting Carbon checked in with Teresa Cheng, California director at Industrious Labs, to talk about passage of AB 1280 and the race to decarbonize manufacturing in the Golden State.

Quitting Carbon is a 100% subscriber-funded publication. To support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or making a one-time donation.

The campaigners, regulators, and companies working to reduce emissions in the industrial sector know it’s time to drop “hard-to-abate” from their lexicon.

Proven technologies exist today that make it possible for even large manufacturers to get off fossil fuels and reduce their emissions.

Dozens of bills were introduced in the most recent session of the California Legislature to ensure the state hits its 2045 carbon neutrality target but one I had missed addresses just the challenge outlined above.

Assembly Bill 1280 (AB 1280), which was signed by Governor Gavin Newsom (D) on October 6, aims to mobilize additional funding to support commercialization of promising clean heat solutions at the tens of thousands of manufacturing sites spread across California.

Specifically, AB 1280 authorizes the California Energy Commission’s Industrial Decarbonization and Improvement of Grid Operations (INDIGO) program to offer grants to clean heat solutions like thermal energy and industrial heat pumps. It also authorizes the California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank’s (IBank) Climate Catalyst Revolving Loan Fund, also known as the Climate Catalyst Fund, to lend to the same projects.

To learn more about the legislation, and the push to decarbonize industrial heat in California, I reached out to Teresa Cheng, the California director at Industrious Labs, a nonprofit that works to decarbonize heavy industries such as steel, aluminum, and cement. Industrious Labs co-sponsored AB 1280.

“We see a prime opportunity in California because we're actually the biggest manufacturing state in the entire country, which folks don't think about,” Cheng told me.

“We have over 36,000 factories across the state, making everything from chips to coffee, wine bottles, medicine and toilet paper. These are products that are obviously used in California but also exported all around the country and even internationally,” she adds.

“Right now, overwhelmingly, to make these products, we burn fossil gas to provide the steam and process heat, and this accounts for most of the climate emissions from manufacturing, and it's also a major strain on public health.”

The industrial sector is responsible for around one-fifth of California’s climate pollution. With bills like AB 1280, state officials are expanding the fight against fossil fuel use in factories beyond a reliance on the carbon price associated with California’s cap-and-invest system.

How serious is California’s new more aggressive industrial decarbonization push? We’ll see next year when lawmakers and Gov. Newsom negotiate funding for AB 1280 in the new state budget.

The clock is ticking. AB 1280 takes effect on January 1, 2027.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What was the impetus behind Industrious Labs and partners like Earthjustice sponsoring AB 1280?

One important thing to note about all this industrial process heat is that there's already commercially available alternatives that don't burn fossil fuels to provide heating for manufacturing processes, things like industrial heat pumps, thermal batteries.

The reason why these technologies are so appropriate is because many of these applications for manufacturing in California are low- to medium process heat. They don't use the heigh temperatures you see in a cement kiln or a steel mill.

AB 1280 renews and upgrades program guidelines for one of the main California state grant programs that provides grants to manufacturers to install this new equipment, the INDIGO program housed at the California Energy Commission.

Although these technologies are already commercially available and being widely deployed in different countries in Europe, in California, we only have a handful of deployments across these 36,000 facilities. What the INDIGO program does is help to de-risk these initial investments for manufacturers that want to decarbonize but need early state support.

There's two main barriers to this equipment being deployed, which is high capital costs – it's still expensive because it's not being widely deployed in the U.S. – and electricity rates in California, amongst the highest electricity rates in the entire country.

The bill supports manufacturers to make this transition, these early movers. It does two main things. It upgrades program guidelines in the INDIGO program. It strengthens some of the labor standards for deployment of these sorts of projects. So, if you receive state funding, you have to agree to certain strong labor and community standards.

The other thing it does is it makes the state's Green Bank, the IBank, its Climate Catalyst Fund also extend loans to industrial decarbonization projects. Traditionally, the IBank’s Climate Catalyst Fund went to transmission or forest management projects. Now, industrial decarbonization projects, like installing an industrial heat pump at a facility to displace gas use, could also receive funding.

To expand on that a bit further, I'm familiar with existing California incentive programs, like the EPIC program at the Energy Commission, that have supported industrial decarbonization. Does AB 1280 touch these programs?

AB 1280 doesn't touch EPIC; it's an INDIGO program. It expands eligibility for thermal batteries, specifically under the INDIGO program. This was a program that we really wanted to focus on building up because INDIGO was created as an industrial decarbonization grant program that focused on projects that were grid beneficial.

Industrial electrification is a huge opportunity, not just for decarbonization of these industrial facilities and being able to improve air quality, especially in environmental justice communities, but also as a resource that could be leveraged to support California's increasingly renewable grid. You'll see a lot of the grantees from the INDIGO program are facilities that because they electrify can now provide demand response or shift a lot of their electricity used to off-peak times.

This is the story we're trying to tell about the opportunity for industrial electrification. It has all these co-benefits that include decarbonizing facilities, cutting climate emissions, improving air quality, creating jobs, but also providing grid resiliency and reliability.

AB 1280 is contingent on funding in the budget. There was no dollar amount specifically mentioned in the statute. To me, the obvious question is: What happens in the budget fight next year?

California’s cap-and-invest program was recently reauthorized and expanded. There's discretionary funding from the program’s auction proceeds that lawmakers will haggle over in future years.

Industrious Labs has pointed out that industrial decarbonization previously received just 1% of available funding from the program’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF). How confident are you that lawmakers and the governor will dedicate substantial funding for AB 1280 in budget fights next year, and in future years?

That's definitely a million-dollar question. We're trying to leverage the broad support and momentum we built around AB 1280 to secure continuous funding from the GGRF for the INDIGO program.

One thing that's unique about industrial decarbonization, and the support for industrial electrification, is the broad, big tent of support it's been able to garner. I've been working in the climate movement for years; I used to work on clean electricity campaigns. And to be frank, it was hard to garner this sort of broad support you get here from environmental justice groups, climate groups, the construction trades, manufacturers themselves because of the broad consensus that this is something that has not been invested in and should be invested in. We're hoping that broad support translates into securing continuous funding through the GGRF.

The other thing I think is interesting is recently, as CARB looks to implement some of the changes with the cap-and-trade reauthorization, they had a workshop a couple of weeks ago where they asked, very pointedly, “Should cap-and-invest dollars go toward industrial decarbonization?”

It's clear state agencies are also seeing opportunity here and thinking about this, and are very cognizant we had gotten all this support from the federal government that's no longer there. The industrial demonstration projects as part of the IRA had actually allocated more than half-a-billion dollars to a couple of large industrial decarbonization projects in California.

The state is grappling with how it fills this vacuum, like you see in a lot of other sectors, too, unfortunately. How do you have targeted policy intervention that's going to support industrial decarbonization that's not just cap-and-invest? For a long time, there was the assumption that cap-and-trade was going to take care of all the emissions reductions needed from the industrial sector, which is the second-largest piece of the pie in terms of climate emissions in California.

Largely, you've seen industrial emissions reduction stall over the last several years. There's an increasing recognition that's been insufficient alone as a strategy for tackling industrial emissions.

AB 1280 passed with just one “no” vote in the Assembly. It had bipartisan support in the Legislature.

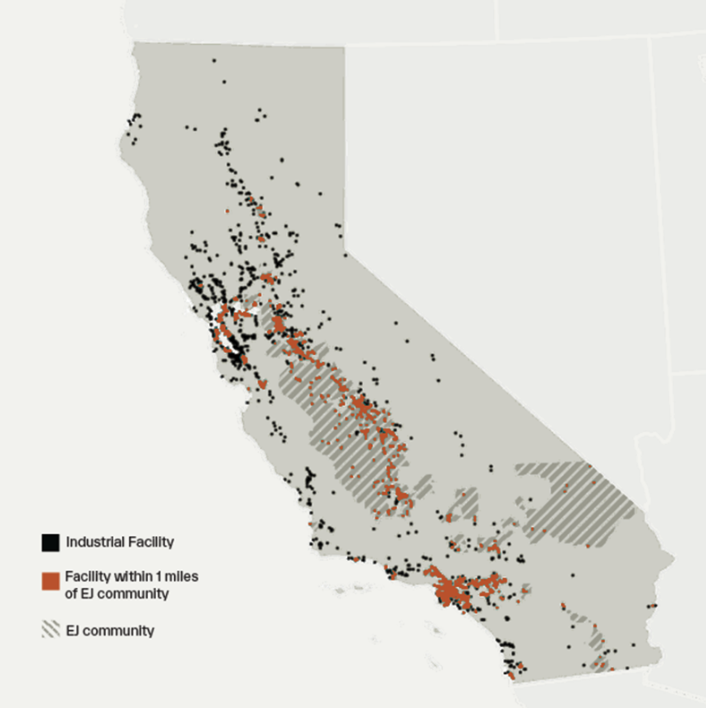

Industrious Labs shared a map recently of manufacturing sites in California laid over environmental justice communities. There were quite a few manufacturing sites in the red rural parts of California, which suggests there should be broad interest in funding these projects across the state.

When you look at the projects that have been funded through the INDIGO program, most of them are in the Central Valley. These are places where you don't have the strictest air quality regulations that are forcing these companies to comply, like you see in Southern California. In Southern California, the air district down there passed the first zero-emissions regulations for small industrial boilers just last year, and so those facilities are going to have to figure out how to modernize and install this new equipment.

Central Valley manufacturers want to modernize their equipment. If the state wants these facilities to make big capital investments and commit to staying in the state for decades to come, this is a smart way to ensure that businesses can stay and thrive in California. They can modernize their equipment. They can keep the jobs here.

A lot of these facilities are the largest employers in those areas. There's a huge economic development angle here. When the federal government pulled out $75 million for the Gallo Glass project in Modesto that was going to install a hybrid glass furnace, that took with it over 100 jobs. Industrial electrification is a commonsense solution the state needs to be investing in to meet its carbon-neutrality goals, but also one that brings with it so many co-benefits.

At the EPIC Symposium last month in Sacramento, the last panel featured executives from startups that have received funding from the EPIC program, and a few of them were thermal energy storage startups.

I heard several times during that panel that although the companies’ technologies were developed in California, they weren't building projects in California. Among the reasons they cited are the electricity tariffs assessed against large industrial customers in California.

Do regulators and the Legislature need to step up to address the problems they cited with these electricity tariffs?

This is one of the greatest ironies of decarbonization across all sectors in California. We have these really ambitious climate goals, and we have amongst the highest electricity rates in the entire country. Not only do we have really high electricity rates, but we have one of the highest spark gaps, the differential between retail electricity costs and low wholesale fossil gas prices that a lot of these manufacturers are accessing. This is perhaps the biggest obstacle to industrial electrification – access to clean, cheap electricity.

The frustrating thing is it doesn't have to be this way. California has very high amounts of very cheap renewable electricity that is continuously being added to the grid, and we're going to be adding more exponentially. As we work toward 100% clean electricity in 2045, the Public Utilities Commission right now, in its demand flexibility proceeding, is looking at how utilities can develop more dynamic rates to encourage demand flexibility.

There's an opportunity for the big private utilities to develop demand flexible rates for industrial customers that can both incentivize industrial electrification and support demand flexibility for the grid to ensure that industrial electrification is grid beneficial. We're about to release a paper with some recommendations on what the Public Utilities Commission and IOUs should be doing in developing industrial rates to do precisely that. Industrial electrification can be largely grid beneficial and should be thought of as a grid asset.

It's not about giving industrial customers a free lunch at the cost of residential and commercial customers but actually developing rate tariffs that more appropriately reflect the reality of what our highly renewable grid looks like today in a way that can drive down overall system costs and actually support rate affordability for residential and commercial customers. This is something we're looking to influence at the PUC, with the IOUs, but also with some of the larger public utilities in California.

There's an opportunity to move forward a strategy in the Central Valley, for instance, where you mentioned having all those red dots. We know there's also a handful of smaller public utilities, like the Modesto Irrigation District, the Merced Irrigation District. This is something that both public and private utilities have in front of them to figure out to unlock industrial electrification.

What are some promising technologies – or promising startups or companies – that could be funded in the future with money unlocked under AB 1280?

What's so remarkable about this field is these technologies are not risky or experimental technologies. These are largely industrial heat pumps and thermal batteries, which is technology that is mature and proven. You have companies like Skyven that have a heat-as-a-service model. A lot of these other companies have heat-as-a-service models, too, which is trying to make the transition as easy and user-friendly for these manufacturers as possible.

These companies like Skyven assume all the upfront capital costs of installing the new equipment. They largely deal with all the maintenance; they're just selling the heat to these companies. There are thermal battery companies like Rondo and Antora that are, as you mentioned, based here in California, and their technology was developed here.

Rondo just unveiled a large new project down in Kern County, which really demonstrates that this is a technology that works and is ready to be scaled up, but just needs the right policy levers through bills like AB 1280, and also electricity rate reform, to be able to meet their full potential in the California manufacturing sector.

One thing to note on electricity rates: I mentioned that rates aren't structured in a way that makes sense with our extremely clean variable electricity grid. California is essentially throwing away, or curtailing, higher rates of power. Industrial electrification is a fix that is meeting this problem that's getting increasingly worse.

A lot of these manufacturing firms are already participating in demand response programs. And they are much more sophisticated than a lot of residential and commercial customers to be able to shift their load, whether that's from installing behind-the-meter resources, installing load, shifting to heat technology like thermal batteries, or shifting some of their production processes. There's a big opportunity here to think about how to leverage industrial electrification as a grid asset. But you really need updating outdated industrial rates to be able to do that.