California wants to accelerate the shift to zero-emission equipment at its ports

Zero-emission cargo-handling equipment is entering the market, but California regulators say additional policies and programs are needed to decarbonize the sector.

Quitting Carbon is a 100% subscriber-funded publication. To support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or making a one-time donation.

Global trade is much in the news thanks to Donald Trump’s single-minded obsession with leveling tariffs on America's trading partners. But comparatively little attention is focused on the climate impact of shipping goods across oceans.

At the end of these intercontinental journeys, goods are offloaded at ports and railyards by cargo-handling equipment such as gantry cranes, reach stackers, side handlers, top handlers, and yard trucks in preparation for last-mile delivery to homes and businesses. Nearly all these machines are powered by diesel engines.

California policymakers have taken notice.

Last month, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) published a draft technology assessment for zero-emission cargo-handling equipment. Guided by a pair of executive orders issued by Governor Gavin Newsom (D) (N-79-20 and N-27-25) as well as recent legislation (AB 617), CARB is working to figure out how to transition California’s 5,000-strong fleet of cargo-handling equipment from models running on fossil fuels to those powered by batteries or other zero-emission alternatives.

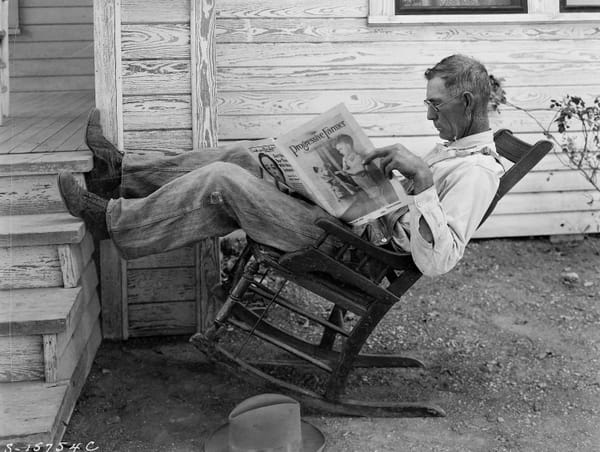

CARB adopted a regulation for mobile cargo-handling equipment in 2005 and fully implemented it by the end of 2017. But the regulation alone will not enable California to meet its air quality and climate targets.

Newsom’s September 2020 executive order (N-79-20) directs state regulators to “develop and propose technologically-feasible and cost-effective strategies to achieve 100% zero emissions from off-road vehicles and equipment operation in the state by 2035.”

According to CARB, the current regulation reduces particulate and NOx emissions through 2037 but after that date progress stalls through mid-century and beyond – after California’s 2045 carbon-neutrality target.

“Despite the progress made under existing programs, additional emissions reductions are needed to protect communities from near-source pollution impacts, help meet the current health-based ambient air quality standards across California, and support the State’s climate goals,” write the authors of CARB’s technology assessment.

The new report is the air regulator’s check-in on the commercial availability and operational feasibility of zero-emission cargo-handling equipment that can replace diesel models. The report evaluates the performance and economics of battery-electric, grid-electric, and hydrogen fuel cell cargo-handling equipment.

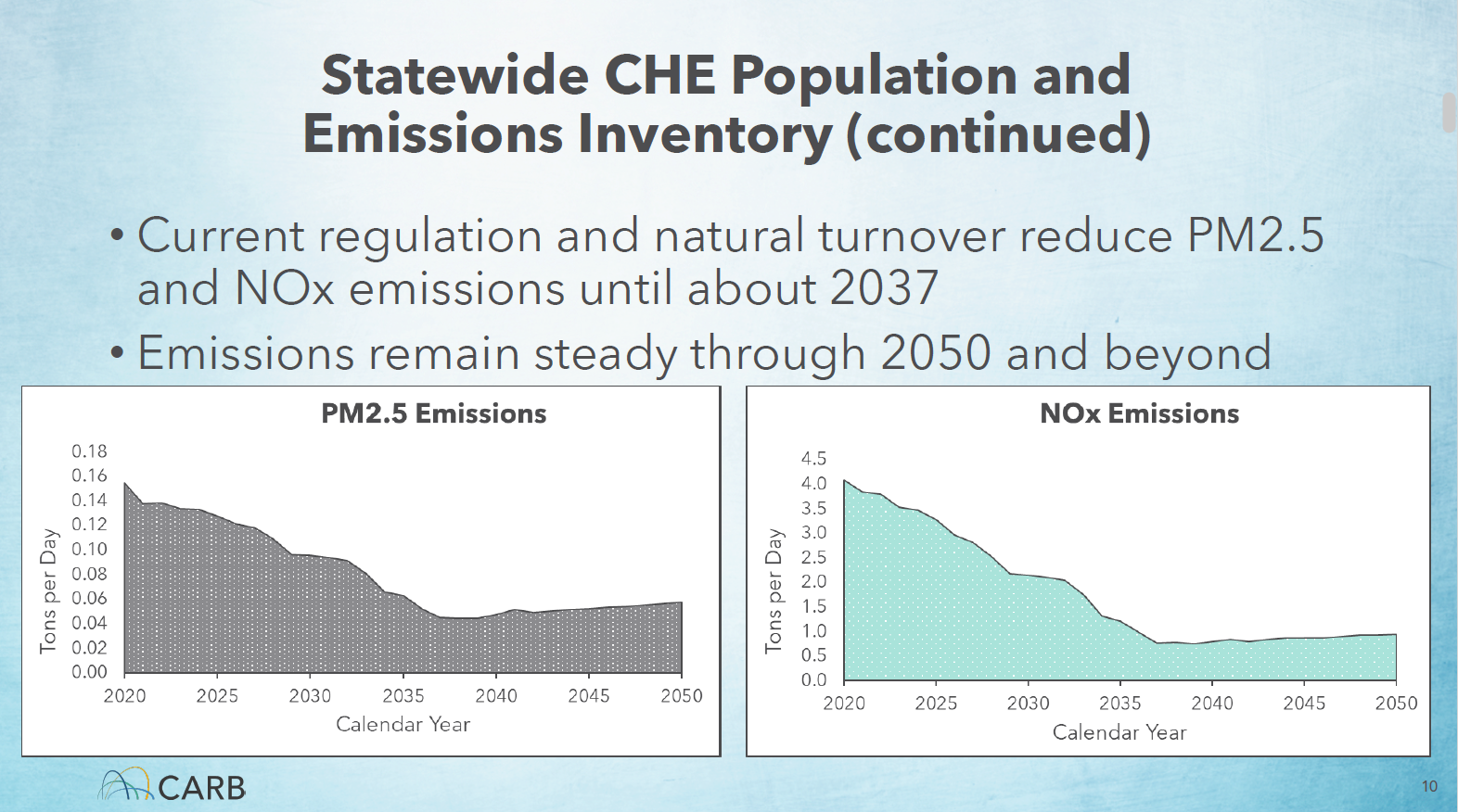

The good news is that of the 25 types of zero-emission cargo-handling equipment evaluated in the report, 24 have commercially available models. And 400 pieces of zero-emission cargo-handling equipment – automated guided vehicles (AGVs), rail-mounted gantry cranes, and ship-to-shore cranes – are operating at California ports today.

But just three types of zero-emission cargo-handling equipment – battery-electric AGVs and grid-electric rail-mounted gantry cranes and ship-to-shore cranes – were given a technology readiness rating of “equivalence” with diesel models. Even more concerning, just two types of zero-emission cargo-handling equipment – battery-electric forklifts and yard trucks – are expected to achieve “equivalence” with diesel models within 10 years given current policies and incentive programs.

For the remaining types of equipment evaluated, the forecast is even bleaker.

“The remaining 20 types of CHE [cargo-handling equipment] (80%), do not achieve Equivalence and require market intervention – including incentives and additional emission reduction strategies – to achieve it within 10 years,” warn the authors of CARB report.

According to CARB, the market interventions could include new or amended regulations, air quality control programs, cooperative agreements, memorandums of understanding, and emission reduction agreements.

California regulators had anticipated an ongoing partnership with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on emissions reductions initiatives at the state’s ports and railyards. The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act had allocated $3 billion for a Clean Ports Program.

As I covered in my January Q&A with the Port of Oakland’s Matt Davis, the port was awarded a $322 million grant under the program to help fund its transition to zero-emissions operations. The port plans to use the grant to purchase nearly 700 zero-emission trucks and other pieces of cargo-handling equipment.

Of course, the second Trump administration’s hostility towards climate and clean energy programs leaves California without a willing federal partner for at least the next three years.

When I checked in with the Port of Oakland in April on the status of its EPA grant, a spokesperson told me the port “continues to receive funding from our EPA Clean Ports grant. We remain confident the program will continue to fund the modernization of U.S. ports to remain competitive in a global market and maintain peak performance and efficiency.”

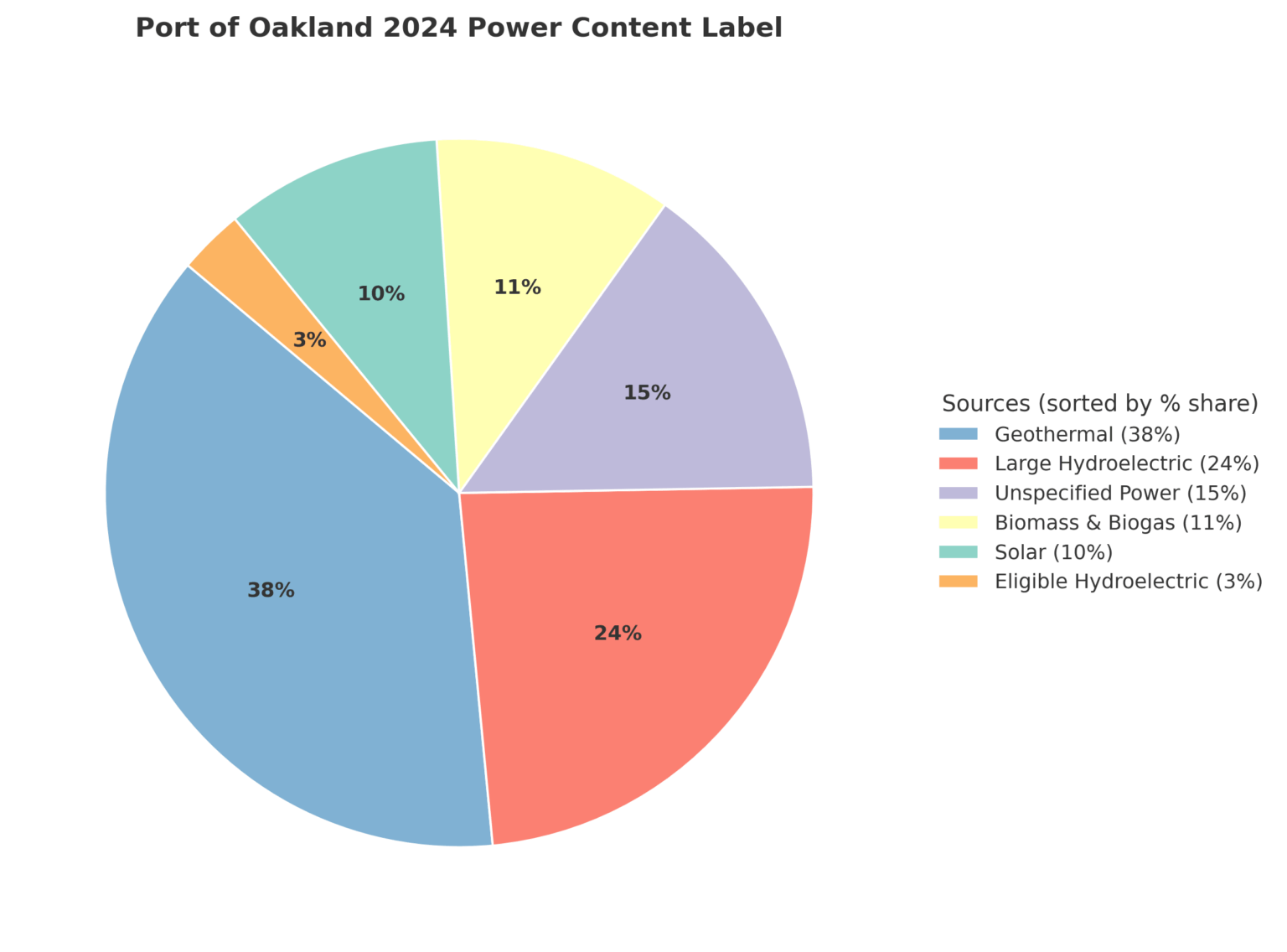

The Port of Oakland is pushing ahead with its goal to become the “cleanest and greenest” port in the country. Last year, a record 86% of the electricity the port provided to tenants and facilities came from renewable and zero-carbon sources. The port also recently signed a long-term energy storage services agreement with the Trolley Pass Project battery energy storage project in San Bernardino County.

The preparations underway at the Port of Oakland for zero-emission operations underscore the challenges ports must overcome to deploy clean equipment that matches the performance and capabilities of incumbent diesel technology.

“The engine power of diesel CHE allows operators to lift and move hundreds of thousands of pounds of cargo daily,” write the authors of the CARB report.

“Diesel CHE is designed to operate reliably for at least 10 to 15 years when serviced regularly. Large fuel tanks allow for several shifts or even days of operation before refilling. Refueling a CHE diesel tank takes about 10 to 30 minutes depending on the type of CHE.”

Government agencies and shipping and logistics companies will need to work together to ensure that zero-emission alternatives can match the benchmarks set by diesel equipment.

“Challenges, such as high costs, infrastructure needs, and reliability must be addressed. A mix of public and private infrastructure is needed to deploy these zero-emission technologies successfully,” conclude the report authors.