Here’s how California plans to reduce emissions from aviation in the Golden State

An early look at draft policies that could be brought to the California Air Resources Board in 2027 to reduce emissions from the aviation industry in the state.

Quitting Carbon is a 100% subscriber-funded publication. To support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or making a one-time donation.

Aviation is one of the most intractable climate puzzles to solve. So, it should be welcome news to policymakers everywhere that California regulators have taken up the challenge of reining in emissions from the sector.

In 2022, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) committed to developing strategies to reduce emissions from aviation. That process is now well underway.

In March of last year, I attended and reported on a CARB forum focused on technology solutions that could curb climate pollution from the aviation sector. Since that meeting, staff have prepared draft concepts for potential programs and policies that could be brought to the agency’s board for action next year.

Earlier this month, the agency hosted a public workshop to share more details about the four concepts under consideration, which focus on airport operations on the ground and at the gate: controlling emissions from aircraft auxiliary power units; reducing emissions from airport ground support equipment; reducing emissions from aircraft taxiing at the airport; and reducing emissions from aircraft takeoffs and landings.

The scale of the challenge

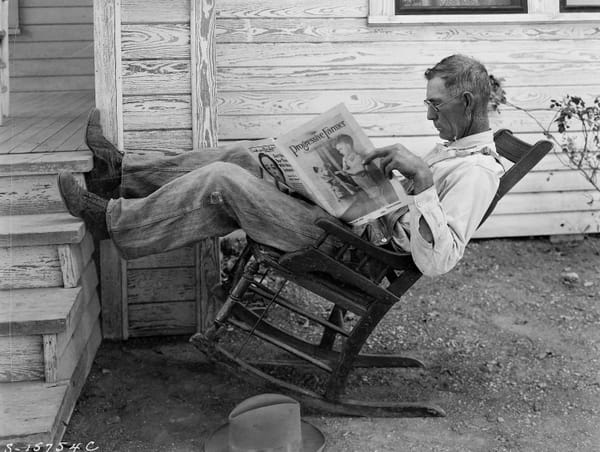

California aircraft activity is projected to increase by two-thirds through 2050, according to CARB. Without additional action, NOx emissions from the sector are projected to increase from 55 tons per day (tpd) in 2024 to 72 tpd by mid-century.

“The aviation sector is the only mobile source category in California where emissions are expected to substantially increase in the future. Certain areas of the state, such as the South Coast Air Basin, are unable to attain federal ozone standards without emissions reductions from aviation,” CARB staff wrote in a report published this month.

“Existing programs remain insufficient to combat the projected increase of aviation emissions,” they concluded.

Four strategies to reduce emissions

Here are the strategies under consideration to check that projected emissions growth. Implementation of the proposed policies could begin as early as 2030.

Auxiliary power units

When parked at the gate between flights, commercial aircraft will turn off their main engines as passengers offload and reboard. But the idle planes still require power to run lights, computers, and the climate-control system.

Pilots will often employ the auxiliary power unit (APU) buried in the plane’s tail to run the electrical systems, even though an increasing number of passenger gates are equipped with infrastructure enabling planes to plug into the airport’s grid connection.

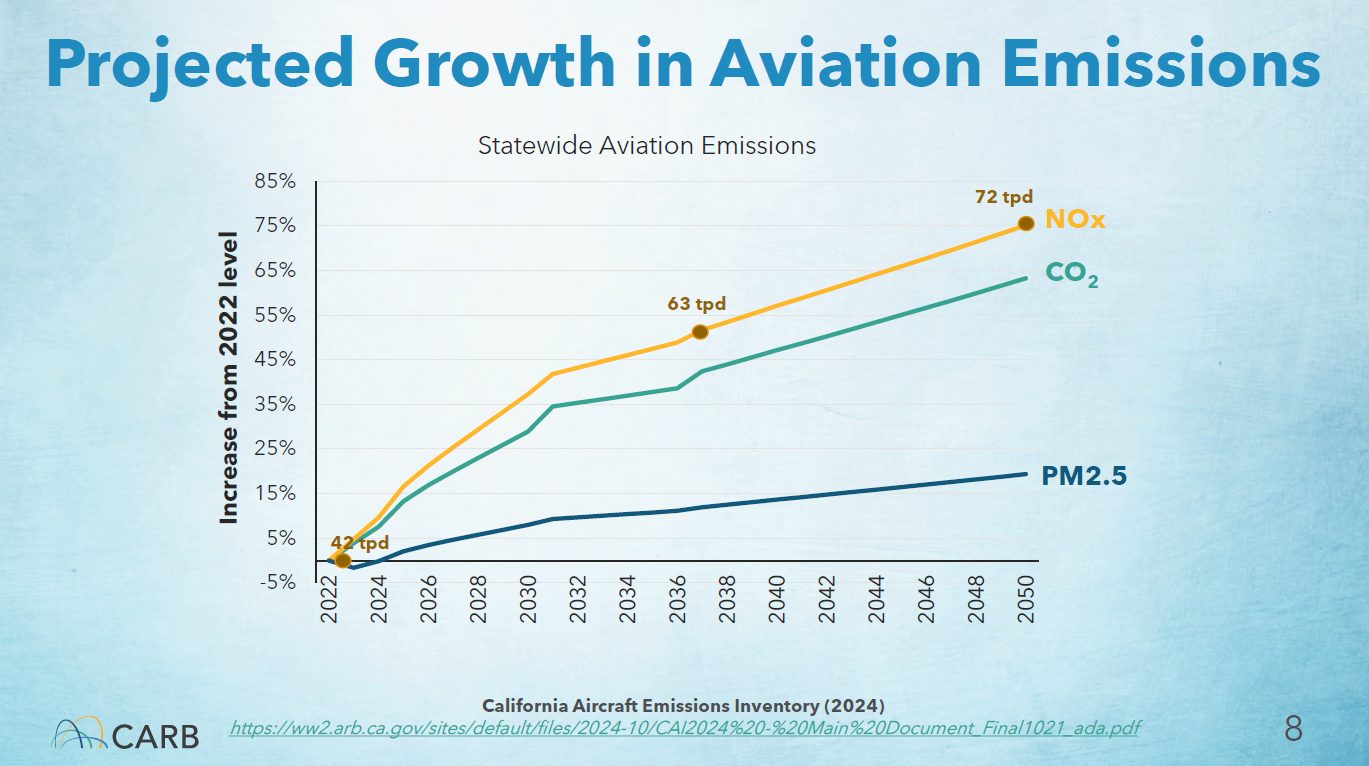

A CARB proposal would require aircraft to reduce emissions from APUs within five minutes of arrival up to 15-45 minutes before departure, depending on the type of aircraft.

During this interval between arrival and departure, the APU would likely be turned off. Planes could connect to fixed ground power at the gate or to mobile ground power units. To keep cabins comfortable, planes could use electricity-powered preconditioned air (PCA) units at gates or mobile PCA units.

The new policy would take effect on January 1, 2032, with airports required to submit infrastructure plans to meet the new rules by July 1, 2030.

Ground support equipment

It takes a diverse fleet of vehicles and other motorized equipment to service commercial aircraft at airports. Think of the belt loaders and baggage tractors, fuel trucks and catering trucks, among many others, you see crisscrossing the tarmac as you wait for your flight at the gate.

The problem is that today most of these vehicles run on fossil fuels. As of last year, around two-thirds of the nearly 14,000 vehicles comprising the total ground support equipment fleet in California ran on gasoline, propane, or diesel, according to a CARB inventory.

That fleet is slowly transitioning to zero-emission models. For example, around half of the belt loaders and baggage tractors in use in California today are electric.

And airports have started to set their own targets to achieve zero-emission service fleets. Airline tenants at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey's airports and Los Angeles International Airport will be required to achieve 100% zero-emission ground support equipment by 2030 and 2033, respectively.

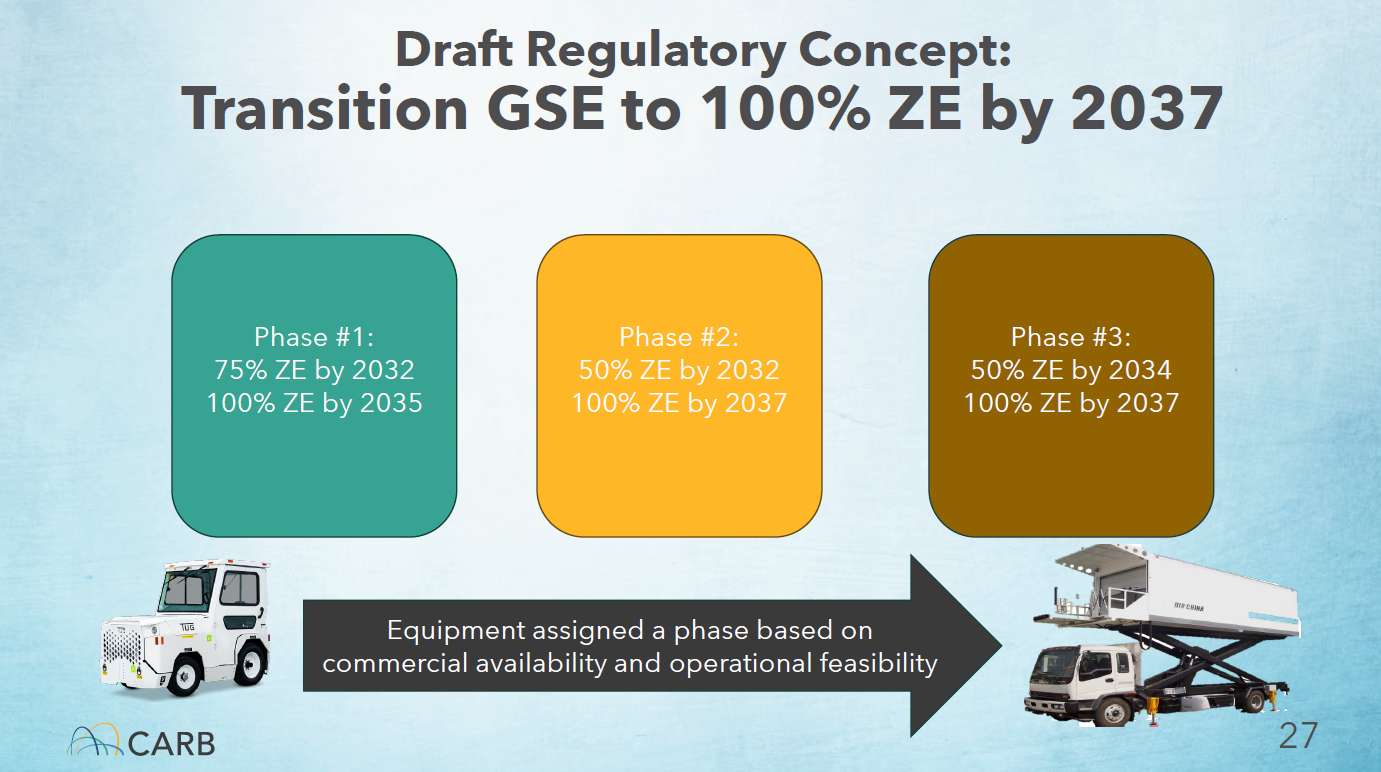

The CARB proposal for California would require a 100% zero-emission ground service fleet by 2037. Equipment would be assigned a more or less aggressive pathway to achieve that target based on the commercial availability and operational feasibility of zero-emission models.

Small motorized carts, belt loaders, and baggage tractors, for example, would be required to be 75% zero-emission by 2032 and 100% by 2035. Larger vehicles such as catering trucks, generators, and hydrant trucks would have until 2034 to hit 50% zero-emission and 2037 to hit 100%.

Aircraft taxiing

The main engines on commercial passenger airplanes burn so much fuel, it pays to turn them on only when necessary. With that in mind, CARB is proposing to limit the amount of time planes employ main engine taxiing and maximize the time of “green” taxiing between the runway and the gate.

As I reported in my dispatch last March, a host of technologies are under development that could assist or take over completely the job of pulling planes to and from gates. The TaxiBot and EcoTug are stand-alone tows that would attach to planes, while the WheelTug and e-Taxi would employ electric motors attached to the nose wheels and main gear, respectively, to reduce emissions from taxiing.

The consultancy Roland Berger is expected to deliver a feasibility study on zero-emission taxiing technologies to CARB by the end of this year.

CARB is considering a two-part plan to reduce emissions from taxiing. Part one could include requirements for single-engine taxiing by 2030. Part two could include an eight-year phase-in timeline to achieve 100% zero-emission taxiing at the state’s dozen largest airports by June 1, 2037.

Takeoffs and landings

One of the primary goals of this rulemaking by CARB is to bring regions of the state, especially the Central Valley and Southern California, into compliance with federal ozone and fine particulate matter standards. Hence the focus in these draft concepts on pollution from operations on the ground and at the gate that harms airport employees and nearby communities.

But CARB is also exploring strategies to reduce emissions from takeoffs and landings at the state’s airports as well. And here, the agency concedes some near-term challenges.

“International and federal emissions standards for aircraft engines are technology-following; aircraft engines have shown little NOx reduction over time, despite federal standards and technology development; and zero-emission technology for large, long-haul, commercial aircraft is still decades away,” writes agency staff in slides presented at the January 15 workshop (emphasis in original).

One strategy being pursued by CARB is what it calls a “Differentiated Landing Fee Program.” Based on schemes operating in Europe, the program would assess revenue-neutral landing fees at the state’s airports.

“California airports would be required to set or modify landing fees based on each aircraft’s NOx emissions per visit,” according to CARB.

Higher landing fees would be assessed on aircraft with higher emissions; lower landing fees would be assessed on aircraft with lower emissions. Larger fees could be assessed against planes visiting airports located in areas out of compliance with federal ozone standards.

The rules would only apply to new planes beginning January 1, 2030.

Achieving near-term climate wins

Electrification could soon make a dent in emissions during flight, especially for flight training and short-haul routes. And CARB signed a partnership agreement with Airlines for America in October 2024 committing to increasing the availability of sustainable aviation fuel for use within California to 200 million gallons by 2035.

The package of policies under consideration by CARB could unlock more immediate aviation decarbonization on the ground and at the gate as solutions for emissions during flight such as solid-state batteries, fuel cells, and sustainable aviation fuels mature and scale over the next decade.