Portland brings zero-emission delivery to its downtown

A six-month pilot project completed earlier this year showcased the potential of zero-emission, last-mile delivery in a 16-block area of downtown Portland, Oregon.

Quitting Carbon is a 100% subscriber-funded publication. To support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or making a one-time donation.

Delivering all the stuff we need to keep the economy humming comes at a cost. There is the price we pay at the register or online, of course, but also on the ledger is the noise, traffic congestion, and pollution that comes with running mostly diesel-powered trucks through our cities.

Freight trucks, delivery trucks, work vans, and other medium- and heavy-duty vehicles make up about 5% of vehicles on the road but account for more than 20% of U.S. transportation greenhouse gas emissions.

But the availability of cheaper, more powerful batteries is making it possible to carry more of the goods we buy in vehicles with no tailpipe pollution.

Nearly one-quarter of the trucks, buses, and vans sold in California last year were zero-emission vehicles. In your own neighborhood, you’ve likely seen all-electric vans from Rivian making Amazon deliveries.

This momentum means that especially for last-mile deliveries, getting goods to the door without emissions is a real possibility.

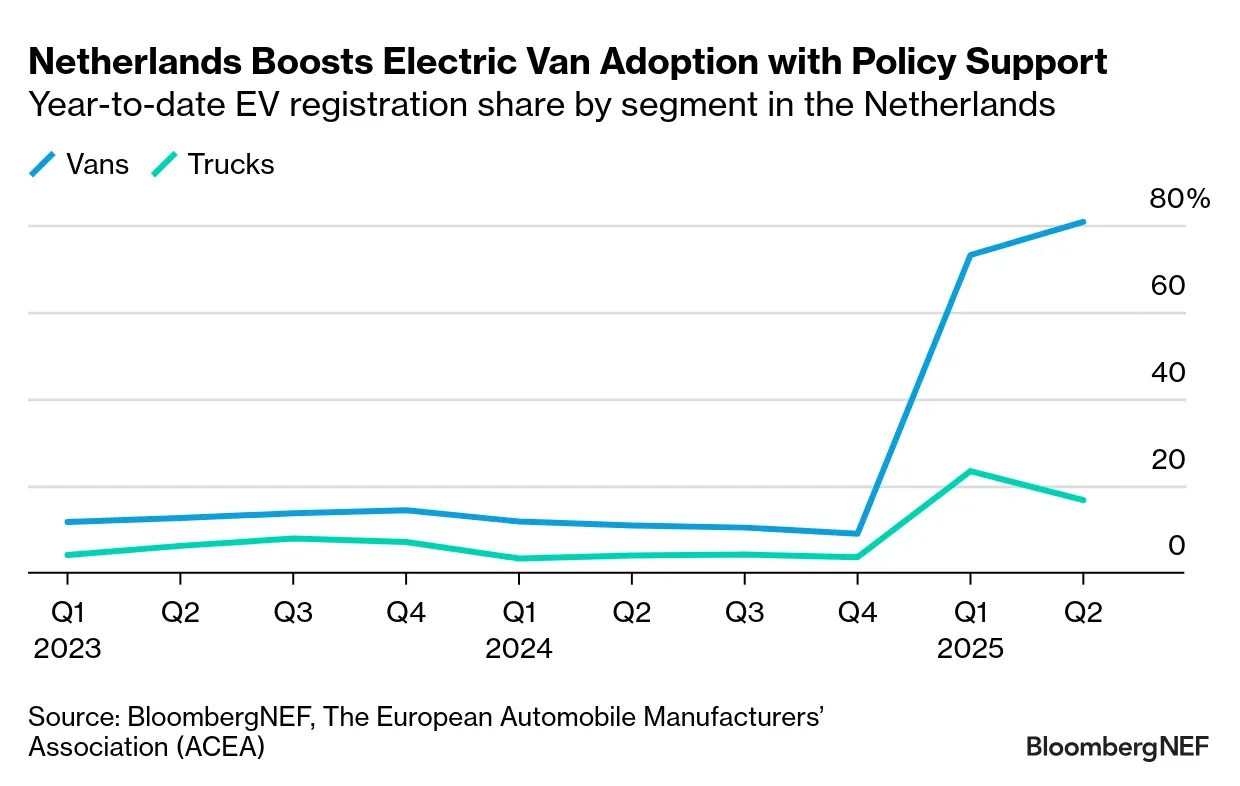

To test this notion, Portland, Oregon, recently established a Zero-Emission Delivery Zone (ZEDZ) in a 16-block area of its downtown “allowing only zero-emission delivery vehicles to use the loading zones in the project area.” The six-month pilot, which was funded by a $2 million grant from the Biden administration’s U.S. Department of Transportation, launched in September 2024 and ran through March of this year.

The Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) released a report last month on successes and lessons learned from the project.

A first-of-its-kind zero-emission delivery zone

Portland was not the first U.S. city to trial a zero-emission delivery zone. Santa Monica and Los Angeles both launched versions of the zones in 2021.

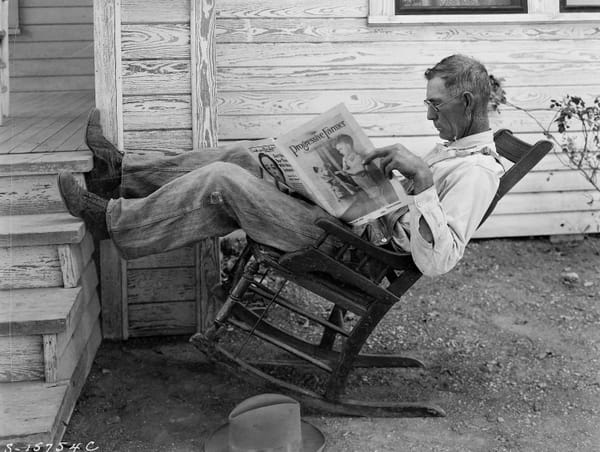

And in Europe, Paris, London, and other large metro areas have established low- or zero-emission zones – designated areas where high-emitting vehicles are either denied entry or charged a fee to enter. Dutch policymakers have gone further and permitted cities nationwide to designate zero-emission zones.

“Electric commercial van purchases skyrocketed in the Netherlands to reach more than 80% of sales in the first half of this year, the highest globally, after the government allowed municipalities to designate urban zero-emissions zones. So far, 18 cities, including Amsterdam, The Hague and Eindhoven, have introduced such zones, with 11 more in planning,” wrote Colin McKerracher, head of clean transport at BloombergNEF, in research published last month.

But the Portland pilot was the first of its kind in the U.S.

“This project piloted the country’s first regulated Zero-Emission Delivery Zones that tested new digital infrastructure tools and offered preferred curb access to encourage the transition of commercial fleets to zero-emission vehicles,” according to PBOT.

“When the pilot was envisioned, the goal was to build on approaches trialed by Los Angeles and Santa Monica,” wrote the authors of the PBOT report. “Portland envisioned a geographic area where … delivery spaces, known as Truck Loading Zones, would be temporarily transitioned to be for zero-emission vehicles only and regulated as such.”

Portland later shifted its terminology so that “Zero-Emission Delivery Zones” “refers to a specific loading space at the curb, of which there could be one or many.”

Rare among U.S. cities, Portland has both adopted a long-term freight plan and dedicated resources to reduce freight emissions.

The effort is not just essential if the city is to achieve its 2050 net-zero carbon emissions target, with freight accounting for nearly one-quarter of Portland’s transportation carbon emissions, it is also intended to bring pollution relief to some of the city’s most vulnerable residents.

“In Portland, nearly 90,000 residents live within 1.2 miles of the city’s biggest sources of air pollution, such as freeways and industrial facilities,” according to the PBOT report.

Project successes

Portland was awarded the U.S. DOT grant in September 2023. By late summer 2024, city transportation officials, working with private sector and academic partners, had installed 16 camera-based parking sensors in the ZEDZ and created a free digital parking permit for delivery companies operating zero-emission deliveries. PBOT launched the pilot on September 19.

After six months, the project had notched successes, according to PBOT: "DHL bought three electric vehicles for deliveries in Portland and installed chargers at their local facility; Amazon rerouted their zero-emission vehicles to be deployed within the project area; the first FedEx-branded zero-emission vehicles in Portland were spotted in the project area; and HYPHN decided to purchase their first zero-emission vehicle for their moving company operations."

The Portland Bureau of Transportation had also promoted the use of electric cargo bikes in the zero-emission delivery zone. B-line Urban Delivery, an e-cargo tricycle-based last-mile delivery service provider, was brought on as a project partner. By the end of the pilot, six new companies had contracted with B-line for zero-emission, last-mile delivery services.

The authors of the PBOT report note that “a UK study estimated 10-30% of trips by delivery and service companies could potentially be replaced by e-cargo bikes.”

Manufacturers are responding to this expected increase in demand for last-mile cargo bike-based deliveries by rolling out new models.

The micromobility startup Also, spun out of Rivian, will supply Amazon “with thousands of its new pedal-assist cargo quad vehicles that are big enough to carry more than 400 pounds of packages and small enough to use a bike lane,” TechCrunch’s Kirsten Korosec reported on Wednesday.

Amazon and Also will customize the electric cargo bike, the TM-Q, for Amazon deliveries in Europe and the United States beginning in spring 2026.

“Amazon has more than 70 micromobility hubs in cities across the U.S. and Europe,” Emily Barber, director of Amazon's global fleet, told Korosec.